The ECTC formed in the mid-1960s, when DC and Maryland attempted to build the ten-lane North Central Freeway right through the heart of DC’s Northeast quadrant. The Freeway was purportedly part of a much larger interstate project. Back in the mid-1950s, fueled by some alchemical combination of increased economic prosperity, a WWII-era “mega-project” mindset, and various automobile-oriented advocacy groups, Eisenhower’s “highwaymen” had begun to draw up and build what we know today as the National Interstate System - that vast network of highways that connects the nation and allows high-speed traffic to flow seamlessly from one city to the next nation-wide. By the early 1960s, many of the rural stretches had been completed, and some cities – like Austin – even featured highways cutting right through the center of town.

Not so in DC. By 1964, I-95, the major highway that runs the length of the East Coast, approached DC from both Virginia and Maryland, but on both sides it stopped abruptly ten miles outside of town at the newly completed Capital Beltway. Drivers wanting to enter the city itself had to leave the highway and navigate its surface streets, which, as DC’s burgeoning population began to spill out into the Maryland and Virginia suburbs and long-distance road travel to and from the city became more common, was causing more than a little congestion. And nothing makes a highway engineer more frustrated than congestion. So the District Highway Department began to plan a network of intra-city freeways. And, when the wealthy, white, well-connected residents of DC’s Northwest quadrant flat-out rejected any proposals to put freeways in their neck of the woods, highway planners slyly relocated freeway plans to Northeast, where the population was poorer, more diverse, less-connected to the usual channels, and thus supposedly less able to resist the overtures of the highwaymen. In late 1964, expecting an open-and-shut case, the Maryland and DC highway departments drew up plans for a ten-lane North Central Freeway through Northeast and hid a small announcement about a public hearing in the back pages of the Washington Post.

Thank god for all those crazy old people with nothing to do but sit around and read back pages of the Washington Post! That first public hearing drew more than 700 furious residents, nearly all of whom were vehemently opposed to the freeway – or any freeway, for that matter. As it turned out, it also kicked off a ten year long struggle to keep the freeway out and bring rapid transit in instead.

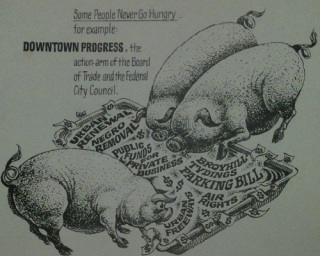

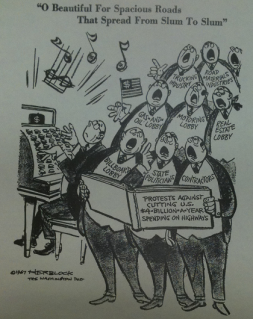

This is where the ECTC comes in. Building on pre-existing neighborhood organizations and leveraging national movements like black power and environmentalism, they mobilized DC residents to protest the freeway, to fight the highwaymen, to testify before congress and to harass the crap out of DC’s Mayor and City Council. They also had some pretty amazing graphic designers on their side. Check this out:

Pigs eating at a trough of highway-related exploitation! Downtown Progress was a business organization that supported building freeways in DC in hopes of bringing suburban dollars back to the city’s central business district:

Those same exploiters doing a number on “This Land is Your Land!” This one vents their frustration at the collusion between big business and politics and the expense of the lives of the people in the path of the highway. And yes, they had lyrics for the entire song.

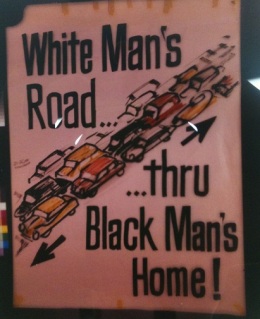

And this one is one of the ECTC’s more famous posters, at least locally, featuring their slogan:

What’s particularly interesting about this last one is that the ECTC quickly grasped the racial implications of moving a freeway from Northwest to Northeast and made race a central part of its campaign against the freeway from the get-go, but it wasn’t until the 1968 riots that the Federal government was willing to admit that a) the ECTC was right and b) in the late 1960s, DC’s integrated neighborhoods had at least as much political clout as its white ones because they had the weight of the entire Civil Rights movement behind them. Really, a genius move on the part of the ECTC.

And, together with all of their other mobilization and communication tactics, an effective one: the North Central Freeway was never built, the Metro’s Red Line runs along the CSX tracks near where the freeway would have been, and the Federal government has long since stopped trying to build highways anywhere near our fine nation’s capital – or in any other major city, for that matter.

These days, it’s better to put those highway funds to good use in building a bicycle network, anyway.

No comments:

Post a Comment