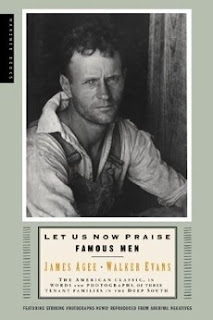

In July and August 1936, James Agee and Walker Evans were working on an article for a New York magazine in which they were to create a "photographic and verbal record" of "cotton tenantry in the United States." In particular, they were to write about "the daily living and environment of an average white family of tenant farmers." As it turned out, finding a "representative" sample of white tenant farmers proved difficult, but they found a group of three families and lived with them for less than four weeks, with Agee creating a written record and Evans taking photographs. The article was not published, and the book went through multiple publishers before finally coming out in 1939.

Let Us Now Praise Famous Men is, as Bill Stott argues, a beautifully-made 1930s documentary; Evans' photos have long since become iconic, and Agee's prose claims the entire beat generation as its descendants. Agee is also careful to situate himself and Evans as characters within the story of the tenant farmers' lives, so that the reader is clear throughout that the book combines objective reality and normative interpretation. The main argument of the book is encapsulated in the verse that serves as its title: "let us now praise famous men, and our fathers that begat us." The tension here is important: while the famous men lead us in creating history and are thus written down and remembered in history books, they are also responsible for the poverty in which his subjects live; while our fathers' names are never known to the world, they are arguably more important, because without fathers there would be no children, no next generation to pass history down to. Thus he celebrates the particularity of the human life of his subjects even as he critiques the universal structures that create it.

Showing posts with label poverty. Show all posts

Showing posts with label poverty. Show all posts

Sunday, April 7, 2013

Saturday, April 6, 2013

96: Bill Stott's Documentary Expression

In Documentary Expression and Thirties America, Bill Stott looks at 1930s America through the lens of the documentary genre. Documentary is a form of expression that purports to represent reality but in which it is difficult for viewers to separate the false from the true. Stott argues that at its base, the 1930s documentary had a left politics, a desire to look not just at the world as it is but at the world of the poor, the downtrodden, and the ordinary, with the intention not just of rendering it vivid and lifelike but also of constructing an audience response or instigating some progressive reform. The different ways people created and used documentaries in the 1930s indicate, to paraphrase Agee, that the world can be improved and yet must be celebrated.

Stott considers a wide range of documentary forms and uses, and shows how documentary conventions were both developed and subverted. Radio, examined through Edward R. Murrow, soap operas, and War of the Worlds, was the "paradigmatic medium of documentary" in the 1930s because it combined the two methods of documentary, "the direct and the vicarious, the unmediated experience and the interpretative commentary" in constant juxtaposition with one another. Photography and documentary films, as Stott shows, were also forms in which apparent reality was actually heavily mediated, particularly when they were made by the government. By contrast, Agee and Evans' Let Us Now Praise Famous Men explodes social documentary by both critiquing the world of the tenant farmers and celebrating it in all its beauty, all well being self-conscious about the role of the narrator in the creation of a work of art that reveals the most intimate details and suffering in people's lives in order to, perhaps, instigate social reform.

While Stott's analysis is somewhat limited by his choice of documentaries - he works primarily with cultural products created by people who worked for the federal government or for private corporations - and while he could do a bit more with the conditions of production, his visual and textual analysis are strong, and his discussion of documentary as a particularly valid entry into American culture in the 1930s makes sense. What better way to see what people might have thought about what their world was like?

Stott considers a wide range of documentary forms and uses, and shows how documentary conventions were both developed and subverted. Radio, examined through Edward R. Murrow, soap operas, and War of the Worlds, was the "paradigmatic medium of documentary" in the 1930s because it combined the two methods of documentary, "the direct and the vicarious, the unmediated experience and the interpretative commentary" in constant juxtaposition with one another. Photography and documentary films, as Stott shows, were also forms in which apparent reality was actually heavily mediated, particularly when they were made by the government. By contrast, Agee and Evans' Let Us Now Praise Famous Men explodes social documentary by both critiquing the world of the tenant farmers and celebrating it in all its beauty, all well being self-conscious about the role of the narrator in the creation of a work of art that reveals the most intimate details and suffering in people's lives in order to, perhaps, instigate social reform.

While Stott's analysis is somewhat limited by his choice of documentaries - he works primarily with cultural products created by people who worked for the federal government or for private corporations - and while he could do a bit more with the conditions of production, his visual and textual analysis are strong, and his discussion of documentary as a particularly valid entry into American culture in the 1930s makes sense. What better way to see what people might have thought about what their world was like?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)