Back in 2004, inspired by my friend

Emily Wismer, I traded my car for a bicycle, and eight years, six cities, and thousands of miles later, I think it's safe to say that I think riding a bike is pretty sweet. I'm rarely stuck in a traffic jam, I get front-row parking pretty much wherever I go, and hey, I get me some exercise and a little daily sunshine, too, especially here in Austin. In these enlightened times, it's generally pretty awesome to be a lady cyclist, too, especially with more and more shops hiring female mechanics (thank you,

Ozone and

The Peddler!), more companies making women-specific gear, and folks like

Mia Birk,

Georgena Terry, and

Shelley Jackson leading the charge in making cycling more accessible to everyone, including women.

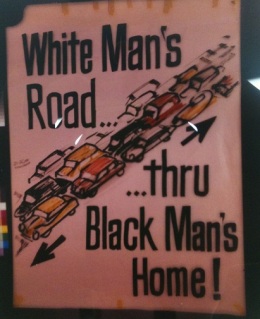

But gender and bicycles can easily become complicated, too, and not just in a turn-of-the-century dress reform kind of way. Back in the 1980s and 90s, technophiles like Donna Haraway argued that technology was going to be the great equalizer, as though somehow the right combination of wheels and gears and metal tubing could erase centuries of gender inequality. As far as bikes go, that hasn't happened - not yet, anyway.

But, with more and more lady cyclists moving into what has so far been a male-dominated technological domain, the bicycle

is beginning to raise some questions about gender, female sexuality, and what it means to be a lady on two wheels. Below, five very interesting answers to these questions.

1. Elly Blue,

Taking the Lane

Elly Blue is a bike activist in Portland who writes about - and advocates for - the need for more bike-friendly (and less misogynistic) cities. Her zine,

Taking the Lane, draws clear parallels between being a cyclist in a car's world and being a woman in a man's world. In its very first issue,

Taking the Lane ranges from road rage and grassroots organizing to fat bias and the condescension women often have to endure from male bike shop employees. Blue argues that women cyclists as both

women and

cyclists are doubly discriminated against, and that only by working together can we end both gender and transportation inequality. I find her writing style intense and thought-provoking and her militancy refreshing - especially since so many of her examples hit very close to home.

2. Peter Zheutlin's

Around the World on Two Wheels and Gillian Klempner Willman's

The New Woman: Annie Londonderry

Gillian Willman's film builds on Peter Zheutlin's long-awaited

Around the World on Two Wheels, which tells the story of Annie Londonderry, the first woman to bike around the world. Back at the turn of the

last

century, Annie Londonderry (who was actually Annie Cohen Kopchovsky, a

23-year old Jewish mother of 3 from Boston), rode a Columbia bicycle

around the world in 15 months - and made $5000 in the process. The whole

thing was a publicity stunt, but Willman and Zheutlin both focus less

on that than on the impact Londonderry's journey had on women's rights.

She left her home, husband, and kids. She wore pants. She sold

pictures of herself. She rented space on her body and her bike to

advertisers. She rode a

bicycle, and she worked it. Capitalism, feminism, and bicycles all in one place. The horror!

3. Rebecca "Lambchop" Reilly

Portable Portrait: REBECCA REILLY (1995) from

Rachel Strickland on

Vimeo.

Rebecca Reilly is the stuff of legend. Not only was she a female courier in the 1990s when there were barely any female couriers to speak of, a badass fixed-gear rider by many (many) accounts, and a woman who insisted she only wanted to be treated the same as a man; she also spent eight years traveling around the United States, working as a courier in Chicago, Houston, Denver, Seattle, San Francisco, Los Angeles, DC, Boston, and New York, and collecting hundreds of oral histories from the couriers she met along the way. In 2000, she compiled many of these stories into

Nerves of Steel, an incredible 300-page rollercoaster ride through the US bike messenger scene in the 90s. The above video is from Rachel Strickland's

Portable Effects project; I could talk for hours about the relationship between bicycles and femininity in it. (I've written a little more extensively about Reilly

here.)

4.

The Dropout's

Bike Taxi Babes calendar

Back in January 2010, I managed to sneak into a photo shoot for

The Dropout's first bike pin-up spread, and being a good (if idealistic) feminist, I spent the rest of that semester trying to fit that night - and the photographs that eventually made it into the magazine - into some semblance of third-wave feminism. It was Elly, actually, who pointed out that not every pin-up has to be feminist, and bikes don't automatically lead to feminist liberation. (Thanks, Elly.) With that in mind, I'm fascinated by

The Dropout's latest project, the Bike Taxi Babes. As far as I know, the ladies pictured are all pedicabbers, and the calendar has more of the flavor of burlesque than pornography;

The Dropout is a pedicab-community organ, and the project is a resolutely for-profit venture. I can't even begin to talk about how this complicates what it means to be a female cyclist.

5. Rick Darge's

Bike <3

bike ♥ from

Rick Darge on

Vimeo.

Rick Darge is a cinematographer who has worked with, oh, I don't know, LCD Soundsystem, Fritos, and Dell, and his video is pretty incredible in its ability to tell a story and capture complex emotions without the main character uttering a single word. The Robert Johnston is a nice touch, too. But while I love this video for its composition, the one thing that truly stands out to me is how adolescently girly it is: how young and innocent Dee looks, how much the camera loves her sweet eyes and hair, how her delicate lace and lingerie contrast with her black socks and Vans. Her love for her bicycle, like Dee herself, is stuck somewhere between childhood innocence and full-grown lady. So what, does she have to cast off all two-wheeled childish things to become a woman? I guess it

is a bit tricky to ride a bike in heels...

... or is it?